A mini-conference. How can such a ‘mini’ name convey so much? So much stress and sleepless nights, so many nervous students ready to faint before stepping on stage and perform their 6’40 show, such a great deal of work and research involved in this ‘mini’ project, so much energy spent on rehearsing again, and again, and again, (and again) so that it will be perfect when the day comes – but don’t be silly, it won’t of course – and the tireless efforts of your other half, who keeps repeating you that your presentation is fantastic, that you are doing a great job, that all you say is absolutely fascinating, that your oral skills can’t be denied by anyone… Hard to follow? Well, that’s really how it went and the pace we had to keep up with for a few weeks. And I say ‘we’ because it was the hell of a teamwork indeed: Elaine H. organised the event, Valentina set up a Twitter page, Ciarán created a website, Elaine M. printed out the programmes and the posters Sean designed… It was a vampiric undertaking that lobotomised us and left us exhausted – but relieved and proud! We made it!

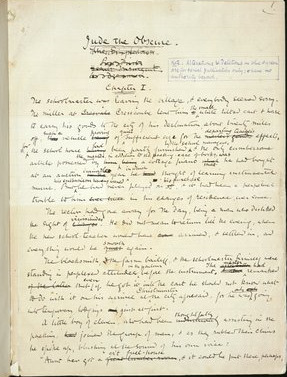

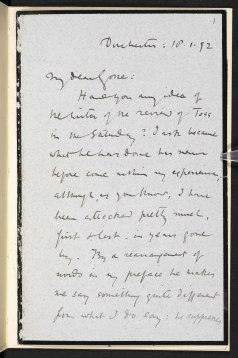

First, intense but so enriching research. We knew we had to deliver a talk about something, but what? Choose a topic that suits you, that you enjoy discussing and about which you may already know a few things. It has to be linked to my end-of-year thesis, doesn’t it? Alright, I’ll be dealing with Thomas Hardy then. But that’s too broad. I must narrow it down if I want it to be doable for me to expose a clear and structured argument in six minutes and forty seconds. What about how his books were received? – since it was a kind of disaster towards the end when he released Tess of the d’Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure – don’t forget he stopped writing fiction as a result. Yes, let’s dig about the reception of the last one, for I would really like to work on this one for my thesis. It might be short enough to be an approachable subject in less than seven minutes, and it’s entertaining – the term funny would show some disrespect for the late author, poor him, as he was truly put out about all that had been said – and I assume not many would know about Hardy and his works, if anyone does. I myself don’t know the whole story lying behind the publication of the book. What? A bishop burnt the book after reading it?…

Powerpoint, Emaze, Prezi, Keynote, we did all we could to enhance our creation. 20 slides of 20 seconds each: a PechaKucha presentation. Make some research, structure your work, find telling pictures that would illustrate your point accordingly, time your speech. Okay, now I have everything ready to start rehearsing. Let’s play it. Wait! I haven’t yet finished with my first part and the time is already up? I have to handle it all over again then. Rewind, rework, press play again. Stop! The third slide has gone too fast, I’m not done quoting here!…

This is how it went until the whole thing had been polished, refined, almost exquisitely executed. And finally the D-Day. First a little detour by the UCC Campus radio for a little talk about Textualities15, just to warm us up! Then enter the intimidating Council room in the Main Quad, UCC, February 27, 2015. Breathe in, breathe out. Here we go! … Is it over yet? It went as quickly as the wait was endlessly tense. What I will remember of it all is an incredible human experience, a blend of knowledge, an engaging range of concerns (poetry, film, drama, fiction, history), a constantly focused attention for our inexhaustibly entertained pleasure. It was worth a never-ending anguish, recurrent stomach cramps, a stubborn headache, weird dreams at night, etc. Although I am obviously glad it’s all over, I would very much like to do it again, because it was more than a useful exercise for me; to me it somehow sounded like the beginning of my career – I know these are big words but that’s how I felt on the spot and still do in hindsight. Simply accept what comes to you. Open your arms. Embrace opportunities. A unique experience we will all remember for sure.

Thank you all very much for coming, staying, performing, listening, reacting, taking pictures…